Home »

Ship named for heroic Saskatchewan nurse

By Elinor Florence

A Canadian naval ship will be the first one ever named after a woman, Margaret Brooke, a nursing sister who grew up on a farm near Ardath, Saskatchewan. She will be honoured because of the bravery she exhibited on the night of October 13, 1942.

On that autumn evening, passengers boarded the ferry headed from Nova Scotia to Newfoundland. The Dominion of Newfoundland wasn’t even part of Canada at the time – but because the war was raging, it was the most highly militarized place in North America.

Of the 192 passengers, 118 were in uniform including Royal Canadian Navy Sub-Lieutenant Margaret Brooke, aged 27; and her close friend Sub-Lieutenant Agnes Wilkie from Carman, Manitoba, aged 42. After a two-week leave, they were returning to their duties at the Canadian naval hospital in St. John’s. They had travelled together on the train from Winnipeg.

The passengers composed themselves for the night aboard the SS Caribou, shown here in this colour postcard from the Maritime History Archives.

The passengers composed themselves for the night aboard the SS Caribou, shown here in this colour postcard from the Maritime History Archives.

The Caribou was an old and respected veteran of this ferry run, the only one between Canada and Newfoundland. Built in Holland in 1925, she was even the subject of this Newfoundland stamp, advertising a nine-hour crossing between Canada and Newfoundland.

Little did the sleeping passengers know that somewhere in the coastal waters, a German submarine, U-69, was lurking.

Little did the sleeping passengers know that somewhere in the coastal waters, a German submarine, U-69, was lurking.

At 3:24 a.m. most of them were lying in their bunks when the torpedo struck. This was no Titanic, where the passengers had time to sing hymns and prepare for their doom. The Caribou’s boilers exploded, and within five minutes she had sunk to her grave 1,500 feet below the surface.

During those five minutes, there was a scene of absolute madness and mayhem. The lights went out and the ferry went down in darkness. Many of those who made it onto the deck weren’t wearing their lifejackets. Only two of the six lifeboats, and about a dozen rafts, made it into the ocean.

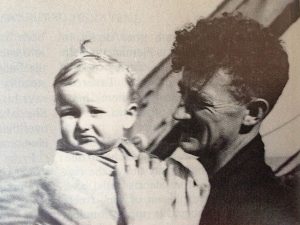

People were throwing themselves off the deck, 16 feet above the icy waves. A baby named Leonard Shiers, one of 11 children on board, was ripped from his mother’s arms by the force of an exploding boiler and both were hurled into the sea.

Margaret Brooke later described her shipmates as “one terrified mob.”

“When the torpedo struck I was thrown across the room right on top of Agnes. I knew what had happened but for a second couldn’t do anything. She jumped up and grabbed the flashlight and climbed up for our life belts,” she wrote in a letter home.

She and Agnes didn’t even make it onto the deck. They forced open their jammed cabin door just as the deck fell away beneath them and they were washed into the sea.

“We were sucked under with her. How we got away from her, I don’t know, but we clung together somehow all the time we were under and when we finally reached the surface, we managed to grab a piece of wreckage and cling to that,” she wrote.

A few minutes later, an overturned lifeboat floated by and the two nurses joined about a dozen other people, clinging to ropes hanging from the side of the lifeboat.

To protect the ferry, the Royal Canadian Navy had assigned a minesweeper to follow it. But in the case of an attack, the minesweeper had strict orders to pursue the submarine rather than pick up the stranded passengers.

To protect the ferry, the Royal Canadian Navy had assigned a minesweeper to follow it. But in the case of an attack, the minesweeper had strict orders to pursue the submarine rather than pick up the stranded passengers.

The horrific scene must have looked something like this shot from the movie Titanic.

Soon, the frigid water brought on hypothermia. By 5 a.m., the survivors began to die.

Agnes was a petite, slender woman who was racked with cramps. Eventually she passed out and let go of the rope, but Margaret hauled her unconscious body back, holding onto the rope with one hand and Agnes with the other.

Finally, a half-frozen Margaret couldn’t hold onto her friend any longer. “I did manage to hold her until daybreak, but then a wave pulled her right away from me. She didn’t suffer, but it was so terrible to see her go.”

It wasn’t until 6:30 a.m. that the minesweeper gave up the search for the U-boat and began to pick up the survivors among the floating dead bodies and debris. Some of her crew jumped into the freezing water to assist the exhausted survivors. Two people died even after being dragged on board.

Baby Leonard’s pregnant mother was rescued in a state of shock, hallucinating. Only four people were still clinging to the overturned lifeboat, Margaret and three men.

Only 101 of the 237 passengers and crew on board survived the ordeal. Among the dead were the ferry’s long-time Captain James Taverner, his son Stanley and his son Harold, who were serving as first and third officers.

One small miracle happened. Just one of the 11 children on board survived – baby Leonard Shiers. His long white flannel nightgown filled with water and kept him afloat long enough to be grabbed by a man named Ralph Rogers, who made it to a life raft and tucked Leonard inside his coat. After they were rescued, Ralph located Leonard’s mother and handed her the baby while she sobbed with relief.

A public inquiry into the sinking found that nobody was at fault, but the navy eliminated night sailings, mainly so that if a boat was torpedoed, rescue operations could take place in daylight. The sinking of the Caribou is considered the worst inshore disaster of the naval war. Agnes Wilkie became the only nurse in all three services – navy, air force and army – killed by enemy action in the Second World War.

Margaret Brooke was born April 10, 1915, in Ardath, Sask., and grew up on a farm. When she was 18, Margaret and her brother, Hewitt, both left to attend the University of Saskatchewan, where Margaret earned a bachelor’s degree in household science, and her brother a medical degree. She went to work as a dietitian at the Ottawa Civic Hospital.

When the war broke out, she enlisted in the navy, and was made a nursing sister. Her brother enlisted as a doctor and served on the HMCS Skeena, ending the war as a Lieutenant-Commander.

After the sinking of the Caribou, Margaret worked in naval hospitals for the rest of the war. For her heroism, she was made a military Member of the Order of the British Empire. The citation reads: “For gallantry and courage. After the sinking of the Newfoundland Ferry S.S. Caribou, this Officer displayed great courage whilst in the water in attempting to save the life of another Nursing Sister.”

After the war, she stayed in the navy, rising to the rank of Lieutenant-Commander before retiring in 1962. She enrolled at the University of Saskatchewan where she studied paleontology, eventually earning a PhD. Never married, she retired and moved to Victoria in 1986.

In April 2015, the Royal Canadian Navy announced it would name one of its six new Arctic patrol vessels the HMCS Margaret Brooke.

It is the first time a Canadian ship will be named for a woman, and the first time for a living person. Margaret Brooke said she was “astounded” when told of the honour. “The navy doesn’t just go around naming its ships after people.”

This is a more recent photo of Margaret Brooke. She did not live to see the ship that will bear her name, since she died in January 2016.

The ship is now under construction and one can only hope that her name will resound through history, just one example of the bravery of our Canadian veterans.

Rest in Peace, Margaret Brooke.

(With information from: Reader’s Digest, October 1992: Last Night of the Caribou, condensed from Night of the Caribou, by Douglas How; and The Globe and Mail, January 31, 2016: “Naval officer Margaret Brooke hailed as hero after wartime attack.”)

Lead image: The future Margaret Brooke AOPS (Arctic Offshore Patrol Ship).

– Career journalist Elinor Florence, who now lives in Invermere, has written for daily newspapers and magazines including Reader’s Digest. She writes a regular blog called Wartime Wednesdays, in which she tells true stories of Canadians during World War Two. Married with three grown daughters, her passions are village life, Canadian history, antiques, and old houses. You may read more about Elinor on her website at www.elinorflorence.com.

– Career journalist Elinor Florence, who now lives in Invermere, has written for daily newspapers and magazines including Reader’s Digest. She writes a regular blog called Wartime Wednesdays, in which she tells true stories of Canadians during World War Two. Married with three grown daughters, her passions are village life, Canadian history, antiques, and old houses. You may read more about Elinor on her website at www.elinorflorence.com.

Elinor’s first historical novel was recently published by Dundurn Press in Toronto. Bird’s Eye View is the only novel ever written in which the protagonist is a Canadian woman in uniform during World War Two. The heroine Rose Jolliffe is an idealistic Saskatchewan farm girl who joins the Royal Canadian Air Force and becomes an interpreter of aerial photographs. She spies on the enemy from the sky and makes several crucial discoveries. Lonely and homesick, she maintains contact with Canada through letters from the home front. The book is available through any bookstore including Lotus Books in Cranbrook, and also as an ebook from any digital book provider including Amazon, Kindle and Kobo. You can read more about the book by visiting Elinor’s website at www.elinorflorence.com/birdseyeview