Home »

Animals that went to war

By Elinor Florence

Thousands of our furry and feathered friends performed valuable work during the First and Second World Wars, while most simply provided love and comfort to servicemen while they were far away from home. Here are just a few examples.

This American soldier, Corporal Edward Burckhardt, is shown here with the kitten that he said ‘captured’ him at the base of Suribachi on the Japanese battlefield, Iwo Jima. This adorable kitten enjoys chilling on the shoulder of an unidentified Royal Air Force fighter pilot.

This adorable kitten enjoys chilling on the shoulder of an unidentified Royal Air Force fighter pilot. The British bulldog came to symbolize tenacity during the war. This bulldog, who looks right at home on a motorbike, was the mascot of a regiment from Quebec that was based in England.

The British bulldog came to symbolize tenacity during the war. This bulldog, who looks right at home on a motorbike, was the mascot of a regiment from Quebec that was based in England. Size doesn’t matter when it comes to serving your country! Smoky, a four-pound Yorkshire terrier, was found in the jungle of New Guinea and purchased by American soldier Bill Wynne. During the war, Smoky earned honours for bravery after she warned her owner of incoming fire on a transport ship.

Size doesn’t matter when it comes to serving your country! Smoky, a four-pound Yorkshire terrier, was found in the jungle of New Guinea and purchased by American soldier Bill Wynne. During the war, Smoky earned honours for bravery after she warned her owner of incoming fire on a transport ship. Hoy (as in Ahoy?) was the mascot of a minesweeper HMS Bangor. Here Hoy is being held by a member of the crew.

Hoy (as in Ahoy?) was the mascot of a minesweeper HMS Bangor. Here Hoy is being held by a member of the crew. This life-jacket wearing spaniel is Butch O’Brien, a spaniel mascot of the U.S. Navy, on board his ship in the Sea of Japan.

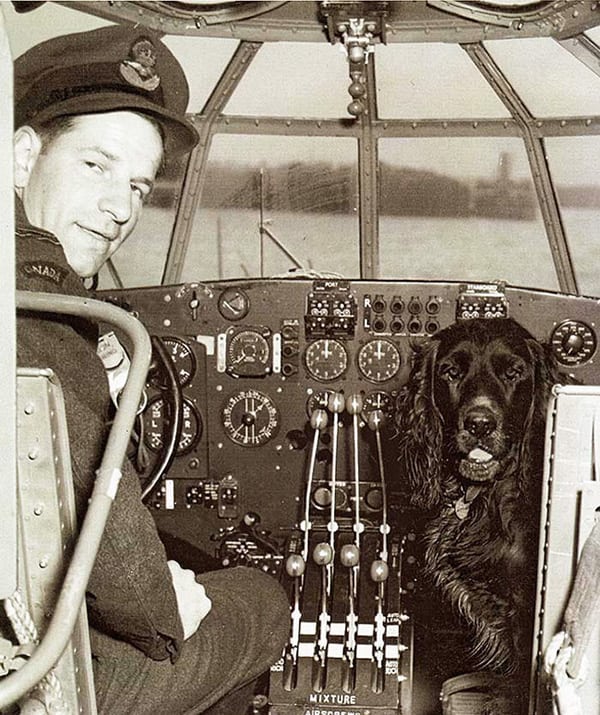

This life-jacket wearing spaniel is Butch O’Brien, a spaniel mascot of the U.S. Navy, on board his ship in the Sea of Japan. Of course, dogs were very popular mascots at air bases throughout Britain during the war. Here’s the Royal Canadian Air Force 422 Squadron mascot named Straddle, taking the co-pilot’s seat in a Short Sunderland flying boat. The squadron’s crew members flew these massive Sunderlands on coastal and submarine patrols and Straddle went on a number of patrols with them.

Of course, dogs were very popular mascots at air bases throughout Britain during the war. Here’s the Royal Canadian Air Force 422 Squadron mascot named Straddle, taking the co-pilot’s seat in a Short Sunderland flying boat. The squadron’s crew members flew these massive Sunderlands on coastal and submarine patrols and Straddle went on a number of patrols with them. Coupie, the canine mascot of a squadron in the Allied Expeditionary Air Force, used to visit each aircraft and pilot to wish them good luck before takeoff. Here he is with Royal Air Force pilot.

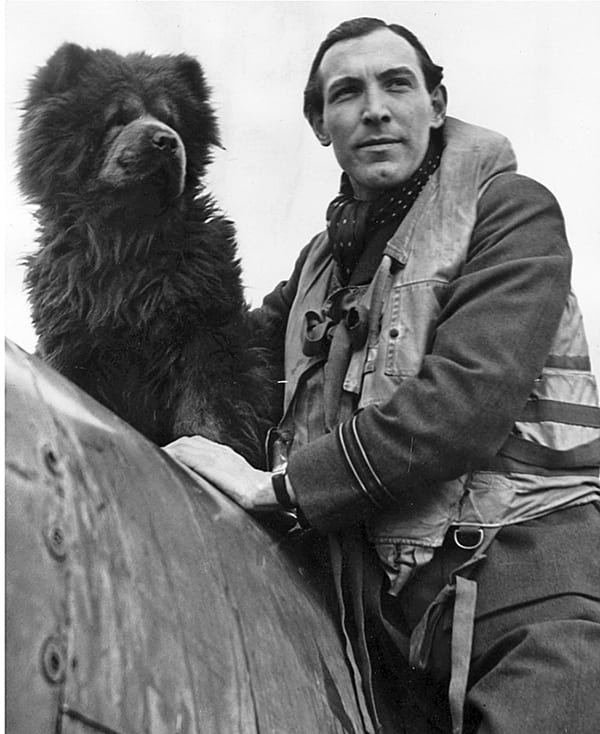

Coupie, the canine mascot of a squadron in the Allied Expeditionary Air Force, used to visit each aircraft and pilot to wish them good luck before takeoff. Here he is with Royal Air Force pilot. Royal Air Force Captain Eric Stanley Lock is seen here boarding his Spitfire with his adorable mascot.

Royal Air Force Captain Eric Stanley Lock is seen here boarding his Spitfire with his adorable mascot. Formerly a ship’s dog on board the HMS Grasshopper, this English pointer named Judy helped save the lives of servicemen after the Grasshopper was sunk. She then spent three years in Japanese prisoner-of-war camps, narrowly escaping death many times. She was the only dog to be registered as a Second World War Prisoner of War.

Formerly a ship’s dog on board the HMS Grasshopper, this English pointer named Judy helped save the lives of servicemen after the Grasshopper was sunk. She then spent three years in Japanese prisoner-of-war camps, narrowly escaping death many times. She was the only dog to be registered as a Second World War Prisoner of War.

Oleg of the Glacier, a beautiful white Samoyed, is shown here on patrol with one of the Canadian soldiers who had adopted him as a mascot.

Another brave canine was Sergeant Stubby, the most decorated war dog of World War One. He was the official mascot of the U.S. 102nd Infantry. Stubby participated in seventeen battles on the Western Front. He saved his regiment from surprise mustard gas attacks, found and comforted the wounded, and once caught a German soldier by the seat of his pants, holding him there until American soldiers found him! Here is Sergeant Stubby wearing his many medals.

Canadian spectators enjoy a baseball game between the U.S. Army and the Canadian forces, at Wembley stadium in London. The Canadians in kilts brought their own canine mascot along.

While these British anti-aircraft gunners scan the sky for incoming enemy planes, their watchdog is keeping his eye on the sky as well.

Pigeons were very useful during the Second World War, when about 250,000 homing pigeons carried messages across enemy lines through the most dangerous situations. The Dickin Medal, the highest possible decoration for valor given to animals, was awarded to 32 pigeons. Here a crew member of an RAF Coastal Command Lockheed Hudson holds a carrier pigeon.

Who says dogs are a man’s best friend? One of the most beloved mascots was Aloysius, a lamb that was adopted by a Royal Air Force squadron.

Lead image: Venus the Bulldog was the sassy mascot of the Royal Navy destroyer HMS Vansittart. Doesn’t he look smart in his naval hat?

– Career journalist and bestselling author Elinor Florence of Invermere has written two wartime books. Her novel Bird’s Eye View tells the story of an idealistic Saskatchewan farm girl who joins the Royal Canadian Air Force and becomes an interpreter of aerial photographs. My Favourite Veterans is a non-fiction collection of interviews whose stories appeared previously on e-KNOW, including Cranbrook’s own Bud Abbott.

Elinor’s new novel Wildwood, about pioneer life in the Peace River, Alberta region, will appear in February 2018. It is available for pre-order now at a reduced price on Amazon. For more information about all three books, visit Elinor’s website at www.elinorflorence.com or call her at 250-342-1621.