Home »

High Flight celebrates 75th anniversary

By Elinor Florence

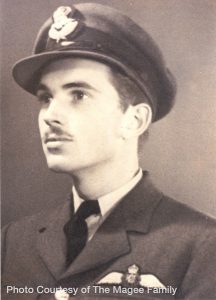

On August 18, Magee family members and countless fans around the world will commemorate the 75th anniversary of the writing of one of the most beautiful pieces of poetry ever composed – ‘High Flight,’ by John Gillespie Magee Junior. A few months after creating his lyrical work of art, the brilliant young Spitfire pilot died in a tragic air accident. He was just 19-years-old.

In the past 75 years, High Flight has become the enduring anthem for airmen everywhere. It never fails to move me to tears, and that’s why I included it in my own Second World War novel, Bird’s Eye View. Take a few moments to read it now.

High Flight

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

Sunward I’ve climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth

Of sun-split clouds, — and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of –- wheeled and soared and swung

High in the sunlit silence. Hov’ring there,

I’ve chased the shouting wind along, and flung

My eager craft through footless halls of air . . . .

Up, up the long, delirious, burning blue

I’ve topped the wind-swept heights with easy grace

Where never lark, or even eagle flew —

And, while with silent, lifting mind I’ve trod

The high untrespassed sanctity of space,

Put out my hand, and touched the face of God.

Did you ever read such lovely phrases as “the tumbling mirth” or “laughter-silvered wings?” Truly, this gifted young man would have done wonderful things if he had lived.

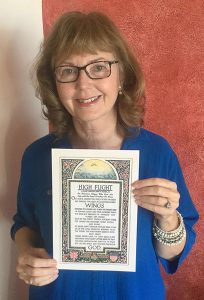

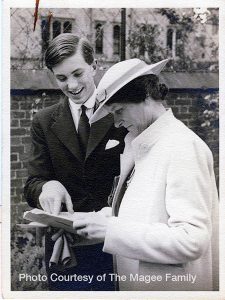

A few months ago, I visited a Facebook event page called High Flight, set up to commemorate the poem’s anniversary. I made a comment there about the poem, and received a response from the poet’s brother, the Reverend Canon F. Hugh Magee in Scotland. We corresponded, and Hugh Magee sent me a laminated copy of this lovely poem, which I will cherish forever.

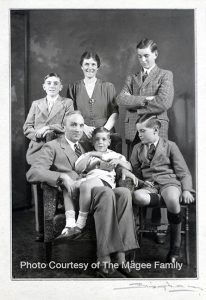

John Gillespie Magee Jr. was born on June 9, 1922 – the eldest son of the Rev. John Gillespie Magee of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Faith Emmeline Backhouse of Helmington in Suffolk, England. The couple met in China where he was an Episcopalian missionary and she was serving as a missionary with the Church Mission Society.

John Senior was an extraordinary man in his own right. Born into a wealthy family, he attended Yale University and then divinity school. After graduation he travelled to China to minister at an Episcopal mission (the American version of the Anglican Church). This became his life’s work, and he remained in China from 1912 to 1940.

In 1937 he witnessed the Japanese invasion of Nanking and the subsequent Nanking Massacre. He was a member of the International Safety Zone Committee that saved hundreds of thousands of Chinese civilians. At great risk to his own safety, Magee filmed and photographed atrocities perpetrated by the Japanese soldiers against the citizens of Nanking, He was later able to smuggle these films out of Nanking, providing evidence of the war crimes that had taken place.

After Magee left Nanking three years later, he returned to the United States and during the Second World War served as Acting Rector at St. John’s Episcopal Church in Washington, D.C., across Lafayette Square from the White House. He officiated at the funeral of President Franklin D. Roosevelt in April 1945.

But it is his eldest son John Junior who is better known to the world. John Senior married his wife Faith in 1921, and John Junior was born in Shanghai in 1922.

John was followed by David in 1925, Christopher in 1928, and Frederick Hugh in 1933. Proud of their origins and wanting to provide their sons with knowledge of their Anglo-American roots, the Magees resolved to send the children to school in England, and then to university in the United States.

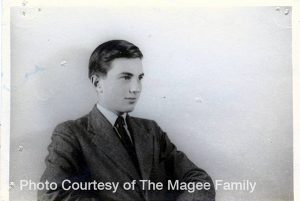

In 1931 their eldest son John, just 10-years-old, was sent to St. Clare’s School, near the family home in Kent, England. In 1935 he was enrolled in the Rugby School in Warwickshire, an institution steeped in English history. (One of his predecessors, William Ellis, in 1873 flouted the rules of football by taking the ball in his arms and running with it, thus inventing the game of rugby.)

Of course John came home to the United States for regular visits with his parents and his younger brothers.

John was deeply moved by the honor roll of Rugby students who had fallen in the First World War, and greatly admired the work of celebrated war poet Rupert Brooke. He was already beginning to show promise as a poet.

In 1939 John won the coveted Rugby Poetry Prize for his poem titled: ‘Brave New World.’

Britain entered the Second World War on September 3, 1939. Having travelled to the United States in 1939 on a family visit, John was unable to return to Britain for his final year at Rugby and therefore completed his schooling at the Avon Old Farms School in Connecticut. While there, at the age of seventeen, he published his first and only book of poems.

It was hoped John would follow the family tradition of attending Yale, and he was admitted for the 1940 freshman class. The United States had not yet declared war against Germany as had England, Canada and the other Commonwealth countries. However, John was eager to defend his mother’s homeland, a country for which he felt much loyalty, so he crossed the border and enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force in October 1940. He was one of thousands of young Americans who joined the Canadian forces prior to 1941.

John received his flight training at No. 9 Elementary Flying Training School at RCAF Station in St. Catharines, Ontario; followed by No. 2 Service Flying Training School at RCAF Station Uplands in Ottawa.

When John came home on Christmas leave in 1940 to Washington, D.C. His family was deeply impressed with what air force discipline had done for John. He returned to Canada to complete his training, and in June 1941 he earned his wings.

Like so many other young flyers, John then made his final visit to his home and family in Washington, D.C. before heading overseas. He was posted to No. 53 Operational Training Unit in Royal Air Force Llandow, Wales to finish his operational training.

While at Llandow, John flew a Spitfire, reaching an altitude of 33,000 feet. This experience evidently made such an impression on him that it provided the inspiration for his best-known work.

During one of these sojourns into the sky, on August 18, 1941, he wrote ‘High Flight,’ destined to become the most famous aviation poem in the world. He sent it home in a letter to his parents dated September 3, 1941, with these words: “I am enclosing a verse I wrote the other day. It started at 30,000 feet, and was finished soon after I landed. I thought it might interest you.”

From Wales, John was assigned to the RCAF’s No. 412 Fighter Squadron, which was formed at RAF Digby, England, on June 30, 1941. The motto of this squadron was and is Promptus ad vindictam (Latin for “Swift to avenge”).

John continued to take part in the daily training exercises that airmen are required to perform, and experienced combat in the autumn of 1941. In that air combat he lost friends to the enemy and fired on an enemy aircraft.

Then on December 11, 1941, tragedy struck. It was not the end that John might have wished – a daring duel with an equally courageous enemy – but rather a tragic accident.

Flying his beloved Spitfire above the Lincolnshire countryside during training exercises, another aircraft, also on a training flight, collided with John’s.

At the inquiry afterwards, a farmer testified that he saw the Spitfire pilot struggling to push back the canopy. The pilot, John, stood to jump from the plane but was too close to the ground for his parachute to open, and died on impact. The other pilot was also killed.

Magee is buried at Scopwick Church Burial Ground in Lincolnshire, England. On his simple white gravestone are inscribed the first and last lines from his poem:

“Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth –

Put out my hand and touched the Face of God.

The popularity of ‘High Flight’ owes much to the fact that the Magees lived in Washington, D.C., at the time of his death. The U.S. had been thrust into the war only days earlier after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Because John was one of the first local casualties, D.C. reporters immediately made their way to his parents’ house for information about the fallen pilot.

At the time, John’s father was Acting Rector of St. John’s Church, and among the materials he provided to journalists was an issue of the church bulletin in which ‘High Flight’ had been published. The poem was widely republished in the following days as part of stories covering John’s death, and it soon came to the attention of poet and Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish, who immediately hailed him as the first poet of the Second World War.

On February 5, 1942, the Library of Congress included Magee’s poem in an exhibition called Poems of Faith and Freedom. ‘High Flight’ shared a case in the exhibit with two noted First World War poems, John McCrae’s ‘In Flanders Fields,’ and Rupert Brooke’s ‘The Soldier.’

‘High Flight’ has become one of the best-known and most enduring poems ever written about flying. It appears in airports and air museums around the world. It is used at services for Remembrance Day, Memorial Day, Veterans Day, and military retirement ceremonies.

Lines from this poem have found their way into films, televisions shows and other pieces of literature, including my own novel. Astronauts have carried copies of it into space and President Ronald Reagan quoted the poem when he paid tribute to the astronauts who died in the space shuttle Challenger disaster 30 years ago. It’s also been set to music.

Three nations – the United States, England, and Canada – all feel a sense of ownership and pride in John Gillespie Magee Jr. In this country, the Vintage Wings of Canada group painted a Harvard aircraft with the markings of one of the Harvards flown by John Magee during his training at Uplands in Ottawa, Ontario.

As for the surviving Magee family members, they experienced the same devastation that so many other families endured during wartime. But although his life ended too soon, John Magee left a legacy beyond that of most mortals.

In a letter to the Royal Canadian Air Force, John’s parents wrote: “We gave our consent and blessing to John as he left us to enter the RCAF. We felt as deeply as he did and we were proud of his determination and spirit. We knew that such news as did come might come. When his sonnet (poem) reached us we felt then that it had a message for American youth but did not know how to get it before them. Now his death had emblazoned it across the entire country. We are thinking that this may have been a greater contribution than anything he may have done in the way of fighting. We will be forever proud of him.”

John’s three younger brothers went on to have long and illustrious careers.

David joined the U.S. Army Air Corps in 1943 and served until the war ended. He later finished his education at Yale and became an investment portfolio manager. He died in 2012 and is buried in the Magee section of Allegheny Cemetery in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Christopher, who also served during the Second World War, worked in the import-export business. He passed away in 2005 and is also buried in Allegheny Cemetery.

Like his brothers, youngest son Hugh was sent to school in England, returned to the United States for further education and to attend Yale University, and then followed in his father’s path and was ordained a priest in England after training at Cambridge. During the past 50 years he has served parishes on both sides of the Atlantic, and currently serves on the staff of St. Paul’s Cathedral in Dundee, Scotland.

Here is a personal recollection from Hugh Magee, who was 11 years younger than his big brother:

“In the summer of 1940, the family had taken a holiday home in the town of Oak Bluffs on Martha’s Vineyard, off the coast of Massachusetts. Mail had to be picked up every day from the main post office and, since our house was located on the outskirts one of John’s daily tasks, as the only member of the family with a driver’s license, was to retrieve the mail.

“On one such occasion John took me along. It was a precious time alone with him. On the way home, while driving along a coastal highway by the harbor (the road is still there) John suddenly pressed the accelerator to the floor so as to push the engine to its limit. Then, with totally uninhibited exuberance, he proceeded to shout at the top of his lungs! It was a thrilling, exhilarating moment for both of us.

“This incident always seemed to me to be reflective of that spirit of exaltation that one finds expressed in two lines of “High Flight”:

I’ve chased the shouting wind along, and flung

My eager craft through footless falls of air . . .

“Be that as it may, my memories of John, though precious few, remain with me and I feel especially close to him to this day.”

Lead image: The High Flight Harvard, Photo courtesy of RCAF.

– Career journalist Elinor Florence, who now lives in Invermere, has written for daily newspapers and magazines including Reader’s Digest. She writes a regular blog called Wartime Wednesdays, in which she tells true stories of Canadians during World War Two. Married with three grown daughters, her passions are village life, Canadian history, antiques, and old houses. You may read more about Elinor on her website at www.elinorflorence.com.

– Career journalist Elinor Florence, who now lives in Invermere, has written for daily newspapers and magazines including Reader’s Digest. She writes a regular blog called Wartime Wednesdays, in which she tells true stories of Canadians during World War Two. Married with three grown daughters, her passions are village life, Canadian history, antiques, and old houses. You may read more about Elinor on her website at www.elinorflorence.com.

Elinor’s first historical novel was recently published by Dundurn Press in Toronto. Bird’s Eye View is the only novel ever written in which the protagonist is a Canadian woman in uniform during World War Two. The heroine Rose Jolliffe is an idealistic Saskatchewan farm girl who joins the Royal Canadian Air Force and becomes an interpreter of aerial photographs. She spies on the enemy from the sky and makes several crucial discoveries. Lonely and homesick, she maintains contact with Canada through letters from the home front. The book is available through any bookstore including Lotus Books in Cranbrook, and also as an ebook from any digital book provider including Amazon, Kindle and Kobo. You can read more about the book by visiting Elinor’s website at www.elinorflorence.com/birdseyeview