Home »

Nurse Jessie Lee treated terrible war wounds

By Elinor Florence

My admiration is boundless when it comes to the wartime nursing sisters who so bravely carried out their grim duties – so it was a delight to interview Jessie Lee Middleton in Abbotsford, British Columbia.

Military nursing in Canada began as early as the Northwest Rebellion of 1885. They followed our soldiers to the Boer War in South Africa in 1899, and then to France in the First World War.

When the Second World War began in 1939, nursing sisters once again answered the call. This time, however, the nursing service was expanded to all three branches of the military: navy, army and air force.

Each branch had its own distinctive uniform and working dress, although all of them wore the traditional white veil. They were respectfully addressed as “Sister” or “Ma’am,” because all were commissioned officers.

By war’s end, 4,480 nursing sisters had enlisted, including 3,656 with the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps, 481 with the Royal Canadian Air Force Medical Branch, and 343 with the Royal Canadian Naval Medical Service.

It was my great honour to visit Jessie in her assisted living facility in Abbotsford. She will celebrate 102 years of a long and productive life on December 12, 2018. I found her to be a gracious and elegant lady, with the dignified bearing that carried her through the horrors of war. This photo shows me with Jessie in her apartment.

Jessie Annie Lee was born on December 12, 1916 in Murrayville, British Columbia – the 12th and last child of farmer James Lee and his wife Edith Brown. When she was born, two of her older brothers were away in France, fighting in the trenches during the First World War. She grew up and attended high school in nearby Langley, B.C.

In those days girls who wanted a career were told to become either a teacher or a nurse – fortunately, that wasn’t a difficult decision for Jessie, who had always wanted to nurse.

She enrolled in the Royal Columbian Hospital’s rigorous nursing program in New Westminster, B.C. In her third and final year, the trainee nurses were dispatched to care for tuberculosis patients at the Tranquille Sanitorium in Kamloops, B.C. This old photo shows the Nurses’ Residence.

Eight months later, Jessie graduated in September 1939 – just one day after Canada declared war on Germany.

Although she wanted to join the army straightaway, she was only 22-years-old at the time, and she had to wait until she was 25. I asked her why other women were able to enlist at the age of 21, but not nurses.

Jessie paused for a moment, and then said: “Not to take any value away from the others, but we nurses had a great deal more responsibility.” I understood what she meant when she described her duties overseas.

She began her nursing career in the maternity ward at the Vancouver General Hospital. Some of her patients were Japanese women, interned as enemy aliens in the old horse barns on the Pacific National Exhibition grounds, and brought into the hospital to deliver their babies.

Jessie was finally able to enlist on September 21, 1942. What a proud moment that was for her!

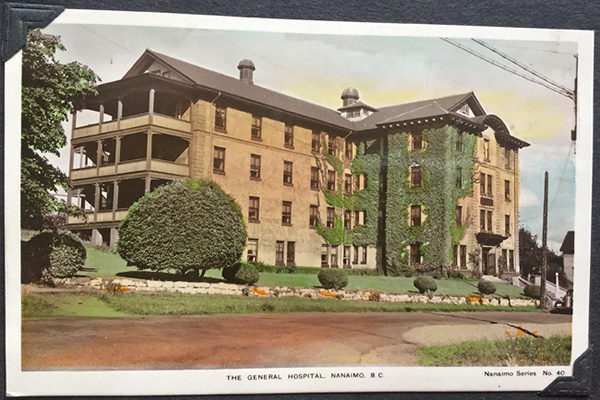

Commissioned as Lieutenant Nursing Sister Lee, Jessie was first posted to a military hospital in Nanaimo, B.C., where most of her cases were related to training accidents or illnesses. “People got sick, you know, even in the army.”

A few months later, she was posted to another military hospital, this one in Prince Rupert, B.C. on the northern coast. Since Canada feared a Japanese invasion, this was a highly defended area. “There were high searchlights placed at the entrance to the harbour, and a net across the harbor to stop the submarines. When the ships came in, they turned off their propellers and drifted across it.” Jessie spent six months there. “This was my first real experience of army nursing.”

The lead image above shows a photo of Jessie on the left with two friends, Mary Dowie and Queenie Rutherford.

Jessie finally realized her dream in March 1943, when she received her orders and joined a contingent of nurses being sent overseas. She was mobilized at Camp Sarcee in Calgary. This photo was taken just before she left Canada.

It was a long, arduous journey. Jessie took the troop train to Halifax with No. 11 Canadian General Hospital. She got off the train and walked a few steps onto the waiting ship that bore them to Greenock, Scotland.

The Queen Elizabeth luxury liner was crammed to the gunwales with thousands of enlisted men. Due to the lack of space, the men spent twelve hours every day on deck, where it was cold and damp. Fog condensed on their woollen blankets, and pneumonia set in.

“Some of them never set foot on English soil – they were carried ashore on stretchers and sent straight back to Canada.”

Jessie was assigned to the No. 7 Canadian General Hospital at Taplow, on the Astor estate, just west of London on the Thames River. There she saw terrible combat injuries for the first time.

“We had one patient – he was recuperated, he was healed – but his face had been burned – if you can imagine it, his eyes, nose, all those parts were gone. He had no ears.”

Shell shock was not uncommon. The frequent sound of the big Allied bombers leaving at sundown to bomb German targets, and returning early the next morning, was particularly upsetting for some patients. “Once they’d hear a plane overhead, they’d go berserk.”

But Jessie’s skills were required even closer to the front. The Allies had taken Sicily the previous year, but had lost 562 Canadian soldiers during the fierce fighting. “Now the Canadian Army was going up the boot of Italy very, very quickly.” Nurses and doctors were needed to treat the wounded.

In July 1944, she sailed from Liverpool to Avellino, a historic town on a plain northeast of Naples, and began to nurse the wounded in a field hospital. The hospital locations chosen had to be accessible from the front lines, since the field medics stabilized the wounded soldiers and sent them back to the hospital by ambulance.

“They would find us a building that would do for us, and then they’d find a better one a few miles up. They were extremely efficient. They needed to find a site that would accommodate 300 beds, for example, plus they assigned so many doctors and nurses and medics for the hospital.” One hospital, she recalls, was a big old Italian abbey.

Jessie’s work led her north to Jesi, an ancient town near the Adriatic port of Ancona. The war was being waged just a few dozen miles to the north and the effects were staggering. “Ancona was horrible – hardly a brick left on a brick. Sometimes it did get to you.”

She did occasionally have leave, and was able to visit cities that had been recaptured by the Allies, including Rome, Florence, and Pisa. She remembers having a picnic on top of the Leaning Tower of Pisa, eating bully beef sandwiches!

“We would share our food packages from home with the Italian civilians. One thing they particularly loved was fish!” This photo from Jessie’s album shows her with an Italian farmer.

While the campaign in Italy wound down, Jessie and her fellow nurses were dispatched to northwest Europe, where the fighting was even fiercer. After the D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944, Canadian troops were battling their way through the Netherlands.

Assigned to a hospital in Nijmegen, Holland, Jessie was as close to the fighting as she had ever been. “The first few nights we heard the sound of battle all the time. They had an attack of gliders. We saw them in the fields where they landed. They were just targets, parachutes caught in the trees. The men were helpless. The Germans would just shoot them.”

As the battle raged, the parade of wounded seemed endless. “They came all night long. They would come up those stairs, clump, clump, clump, and to the beds.”

Sometimes German prisoners were treated along with the Canadians. There was a reciprocal agreement that the patients would be exchanged when they were well enough.

“They were just patients, never an enemy,” Jessie explained. “I remember one young German boy. I swear he must have been 15. He had an abdominal wound . . . he was to have nothing by mouth. And you’d turn your back, and he’d somehow got a little something from someone else’s table. But he was a lovely little fellow, blonde, blue-eyed. He was mischievous. It was just a lark for him.”

For the most part, her daily duties were tragic and emotionally draining. “Every once in a while we would have one who was badly, badly wounded and was not going to survive. You just had to let them die. It was miraculous that their heart was still beating, but there was no way to lead them out of their misery. They’d just lie there till they died. You’d keep their mouths moist; there was nothing else you could do.”

Jessie paused again, clearly emotional.

“Some of them were so seriously wounded that they couldn’t be moved, and we became quite fond of them. They were only kids. The thing to me that hurt so much, was that they were so young.” She repeated: “They were so young.”

Jessie remembers the day the long war ended. “We had either gone to a show or a party or something. We came out of that building and they were snake-dancing through the town. The lights were on! I thought they had to be crazy! What had happened? Of course, I couldn’t believe that peace had come. It seemed like it would never come.”

Jessie spent two months at Oldenburg, Germany, before sailing back to Canada that fall on the Rotterdam. She enrolled in the nursing program at McGill University and began dating Frederick Turner Middleton of Salmo, B.C., a veteran of the Loyal Edmonton Regiment. They had met several times during the war, and now it was time to become serious.

Their wedding took place on Boxing Day 1947, in Murrayville, B.C.

Jessie gave up nursing when she married, and became a devoted wife to Fred and mother to two children: Kathie Middleton McGillivray of Surrey, B.C.; and Bob Middleton of Creston.

Fred’s position as a school superintendent took them to several locations around the province, and then to Abbotsford in 1974. For years she put her training to good use by volunteering with the Abbotsford Hospice Society.

On July 18, 2012, Jessie Lee Middleton was presented with the Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal for her service to her country. She still owns her wartime nursing cape, a very cherished possession.

Thank you so much, Jessie, for the great personal sacrifice you made on behalf of our Canadian soldiers. God bless and keep you.

Jessie’s story appears in a collection of veteran interviews titled My Favourite Veterans: World War Two’s Hometown Heroes. Elinor has also written a bestselling novel about a prairie farm girl who joins the air force in World War Two, Bird’s Eye View. Her new novel Wildwood is about a young woman from the city who inherits an abandoned farm in northern Alberta. Please email Elinor at [email protected] to purchase signed copies of her books, or visit her website for more information: www.elinorflorence.com.