Home »

One million ‘Rosie the Riveters’ in Canada

By Elinor Florence

Rosie the Riveter, the American girl with the red kerchief and the bulging biceps, is an iconic image. But Canada led the way with our own glamourpuss: Ronnie, the Bren Gun Girl (pictured above). She was just one in one million Canadian women who worked in factories during the war!

Rosie the Riveter, the American girl with the red kerchief and the bulging biceps, is an iconic image. But Canada led the way with our own glamourpuss: Ronnie, the Bren Gun Girl (pictured above). She was just one in one million Canadian women who worked in factories during the war!

When the Second World War drained many countries of their working men, somebody had to do their jobs. Not only were thousands of pre-war positions empty, but an entire new industry sprang up: building military aircraft, vehicles and weapons.

Women were urged to take off their aprons and start punching a time clock. Not surprisingly, British women paved the way. This island country was fighting for its survival, and needed all hands to assemble the weapons used to defend itself against enemy invasion.

Canada soon followed suit. By war’s end, nearly one million Canadian women were working in factories. (That’s a staggering figure when you realize that our total population in 1939 was just over eleven million.)

Veronica Foster, also known as Ronnie, was discovered by the National Film Board in May 1941. This 21-year-old came to represent Canadian women factory workers, because she was efficient at her job, but still ultra-feminine.

(Incidentally, her daughter later said that Ronnie didn’t smoke, but the photographer asked her to smoke because it made her look cool and sexy!)

(Incidentally, her daughter later said that Ronnie didn’t smoke, but the photographer asked her to smoke because it made her look cool and sexy!)

Ronnie was one of 14,000 women who toiled at the John Inglis Co. Ltd. in Toronto, producing Bren light machine guns on a production line. And she became known as “Ronnie, the Bren Gun Girl.”

Ronnie was soon catapulted into the public eye. Here’s an article in the June 28, 1941 issue of my favourite Star Weekly magazine, showing Ronnie at work.

And below is a photo of Ronnie going out for a night on the town, looking glamorous after her day spent building machine guns.

Ronnie was featured on the front page of the New York Times in an article dated October 4, 1941 – two months before the U.S. entered the war – as part of a story on how Canadian women were working for the war effort. Speculation is that she served as the model for a similar popular figure that later became known as Rosie the Riveter.

This term first appeared as a song title in 1942 titled “Rosie the Riveter” by the Four Vagabonds.

Also in 1942, Pittsburgh artist J. Howard Miller was hired to create a series of morale-boosting posters. He based his “We Can Do It!” poster on a photograph of Michigan factory worker Geraldine Doyle. At the time of this poster’s release, the name “Rosie” wasn’t associated with this image.

Also in 1942, Pittsburgh artist J. Howard Miller was hired to create a series of morale-boosting posters. He based his “We Can Do It!” poster on a photograph of Michigan factory worker Geraldine Doyle. At the time of this poster’s release, the name “Rosie” wasn’t associated with this image.

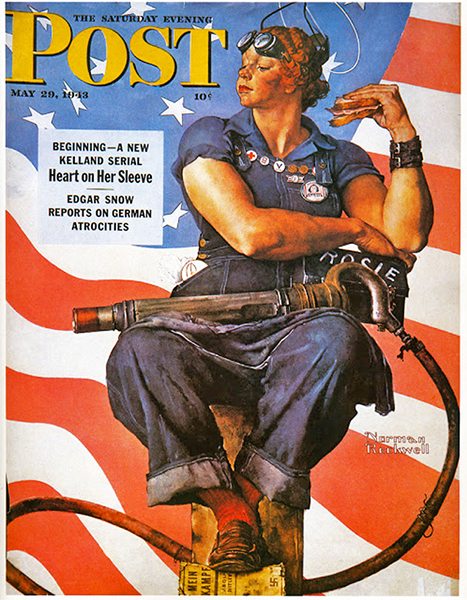

Illustrator Norman Rockwell then created his version of Rosie for the May 29, 1943 cover of Saturday Evening Post. It was the first time the name “Rosie” became associated with wartime factory workers. I love Rockwell’s version of this tough cookie carrying a tin lunch bucket with her name on it!

Dozens of photographs were taken of women looking glamorous on the assembly line, so everyone could be assured that they weren’t losing their essential femininity. Although these photos were clearly staged, they were real American factory workers.

Dozens of photographs were taken of women looking glamorous on the assembly line, so everyone could be assured that they weren’t losing their essential femininity. Although these photos were clearly staged, they were real American factory workers.

Below Mary Betchner inspects a howitzer shell at the Milwaukee, Wisconsin plant of the Chain Belt Co. in February 1943. Her son was in the army; her husband was in war work.

A woman wearing Rosie’s signature red kerchief over her hair inspects an aircraft engine for North American Aviation in June 1942. (Alfred Palmer, Office of War Information)

A 1942 aircraft worker at the Vega Aircraft Corporation in Burbank, California. (David Bransby, Office of War Information)

A welder at a boat-and-sub-building yard adjusts her goggles, October, 1943. (Bernard Hoffma, Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images).

Engine installers at Douglas Aircraft factory in California, October 1942, working on a bomber. (Alfred Palmer, Office of War Information)

Women from Australia and New Zealand were urged to take factory jobs, too. Here’s an Australian poster showing the factory worker in overalls and the ubiquitous kerchief (designed to keep flowing locks out of the machinery).

Russian women were also pressed into action, which is no surprise. Since the Revolution, they were supposedly treated as equals to men. It would be considered an insult to emphasize their femininity. In fact, they were more likely to be using machine guns than building them.

Japan didn’t even wait until attacking Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Their women were counting bullets in this photograph taken several months earlier.

Hitler initially promised that German women would be protected from the horrors of war. Their sphere of influence was Kinder, Küche, Kirche, meaning “Children, kitchen, church.”

But that lasted only until 1943, when Germany simply ran out of foreign workers drafted from the nations it had occupied. (Besides, would YOU trust a conquered people to manufacture weapons being used against the Allies?)

But that lasted only until 1943, when Germany simply ran out of foreign workers drafted from the nations it had occupied. (Besides, would YOU trust a conquered people to manufacture weapons being used against the Allies?)

The future was looking pretty black for Germany, so they did the same as everyone else: declared “total conscription.” The government told women to join the armed forces and work in factories.

Finally, after six long years, the men came home and the women returned to the kitchen and the nursery, as shown by the number of babies born in every country including Germany.

But the taste of money and freedom that women experienced led to the women’s liberation movement of the 1960s, when once again, Rosie the Riveter became a popular image.

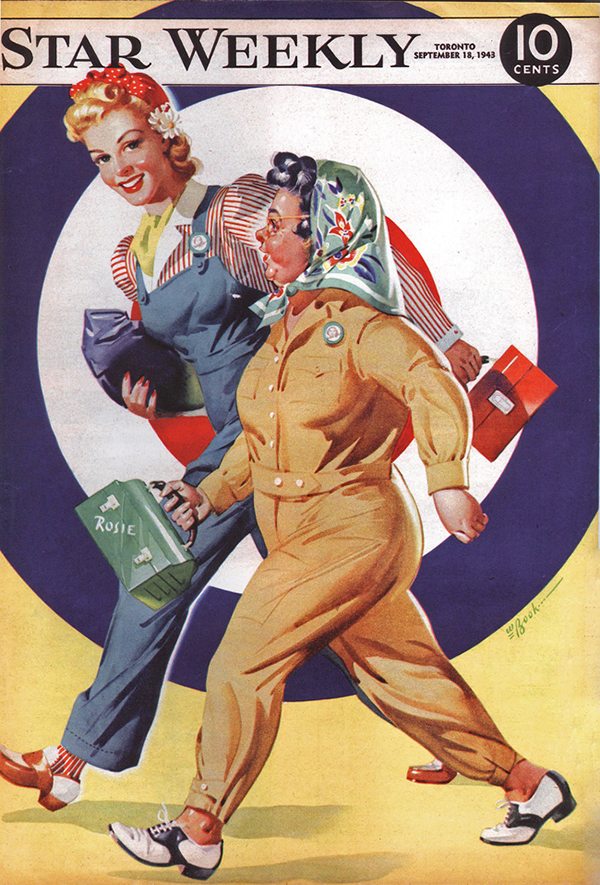

This cover from the Star Weekly magazine really tells the tale of Canadian woman. They weren’t all glamorous. Many of them were hard-working mothers who left the kids with a sitter while they went out to help win the war. Thank you, Bomb Girls everywhere, for your blood, sweat and tears!

– Career journalist and bestselling author Elinor Florence of Invermere has written two wartime books. Her novel Bird’s Eye View tells the story of an idealistic Saskatchewan farm girl who joins the Royal Canadian Air Force and becomes an interpreter of aerial photographs. My Favourite Veterans is a non-fiction collection of interviews whose stories appeared previously on e-KNOW, including Cranbrook’s own Bud Abbott.

Elinor’s new novel Wildwood, about pioneer life in the Peace River, Alberta region, will appear in February 2018. It is available for pre-order now at a reduced price on Amazon. For more information about all three books, visit Elinor’s website at www.elinorflorence.com or call her at 250-342-1621.