Home »

Wartime vet Iris Porter served in burning Egyptian desert

By Elinor Florence

It was a true pleasure to chat with 97-year-old Iris Porter of Calgary, Alberta, about her five years in the British air force. Iris has a razor-sharp memory with an uncanny ability to recall dates and people and places.

It was a true pleasure to chat with 97-year-old Iris Porter of Calgary, Alberta, about her five years in the British air force. Iris has a razor-sharp memory with an uncanny ability to recall dates and people and places.

I also enjoyed the novelty of speaking with a British veteran. My focus is on Canadian veterans, but sometimes I think that people who immigrated here after the war have been overlooked because they didn’t serve in the Canadian forces, and they haven’t been honoured by their own countries, either.

Although Iris has been a proud Canadian resident since 1948, longer than I have been alive, nobody has ever interviewed her before about her service record!

The Early Years

Iris Audrey Inwards was born September 19, 1920 in Richmond, Surrey, England – the third of six children. Her father served in the merchant marine and her mother was a nurse. After finishing school, Iris worked as a clerk in the head office of a women’s dress company in London until she enlisted in the air force on January 2, 1941.

“I wanted to join the WRENs (Women’s Royal Naval Service) because my father had been in the navy, but all they had openings for were cooks and waitresses, so I went across the road and joined the air force instead. I’m so glad I did.”

Iris serves in England

Six months later she was called up, in June 1941. Iris did her basic training in Gloucester and was then posted to RAF Scampton in Lincolnshire.

“I began there as an orderly and worked as the Camp Messenger. I had the secret messages in a leather pouch attached to my wrist, and I ran them around from office to office.”

At right is Iris wearing her smart blue air force uniform.

At right is Iris wearing her smart blue air force uniform.

She was then sent to RAF Leighton Buzzard where she was trained to become Clerk, Special Duties. Also known as plotters, these were the women who stood at a giant map table and pushed the model aircraft around according to their positions in the air, sort of an early form of air traffic control.

When she finished her course, Iris began working as a plotter at RAF Barton Hall near Preston, Lancashire. However, this proved to be emotionally draining for the softhearted Iris. “I couldn’t stand it. We got to know the boys in Preston, and they were here one day, gone the next. It made me very sad, so I decided to re-muster into Pay Accounts.”

After being trained in South Wales, she was posted to RAF Church Lawford in Warwickshire, where she did the pay ledger for about fifty WAAFs on the base, who served in a variety of trades such as parachute packers, flight mechanics and shorthand typists. They slept in metal Nissen huts. “Ours was the last hut on the corner, so we asked the carpenter to make a sign and we put it up. We called our tent “Wit’s End.”

One of her fondest memories is the time she was about to go on a 48-hour leave, and a Canadian pilot trainee named Sloan gave her a tin of strawberry jam. “It was Empress jam, in a gold tin with a picture of a ship on the side. I took it home to my family and we all enjoyed it so much.” At the time, sugar was rationed and sweets were very difficult to find.

Still, Iris longed for greater adventure. In 1944, she and her best friend Kathleen Britain volunteered for overseas duty. They had to make a two-year commitment and they knew they couldn’t come home until it was over. “I knew it would be a risk, but we talked it over and decided to volunteer.”

Iris sails for the Middle East

They began their great adventure on March 25, 1944, when they sailed from Liverpool on the HMS Alcantara, joining a convoy in Scotland and heading south. Eight girls shared a single cabin, sleeping in four double bunks, for the next three weeks as they headed for their unknown destination, past Gibraltar, and into the Mediterranean Sea.

“We passed Tangier in Morocco at night, and the captain told us to go out on deck and look at the lights. We hadn’t seen a city lit up at night for years, because of the blackout at home. It was such a lovely sight.”

The ship turned south at Port Said and entered the 200-kilometre Suez Canal, docking at the foot of the canal in Suez, Egypt on April 9, 1944.

That was the beginning of Iris’s two-year stint in the Middle East. From Suez they took the train about 140 kilometres west to RAF Almaza, just outside Cairo, where they were vaccinated for tropical diseases and given their kit – three skirts and three shirts in beige Egyptian cotton, ankle socks (since the temperatures reached 104 degrees Fahrenheit, it was too hot for stockings), and sandals, which they quickly ditched in favour of more serviceable leather shoes.

Iris was posted to a base called RAF El Gedida in Heliopolis, an ancient city also known as City of the Sun, just east of Cairo. There she worked in the Base Accounts Office, doing payroll and other accounting duties for hundreds of Royal Air Force servicemen and servicewomen stationed throughout the Middle East, including Cyprus, Malta and Italy.

There were 30 airwomen on this base, composing the First Draft of WAAFs – the very first contingent of volunteers.

“We were sent out to replace the married men who hadn’t been home for three years. Of course, some of us were married women as well, and some of us were already widows.”

Here’s a photo of Iris on the right and another WAAF outside the Base Accounts Office.

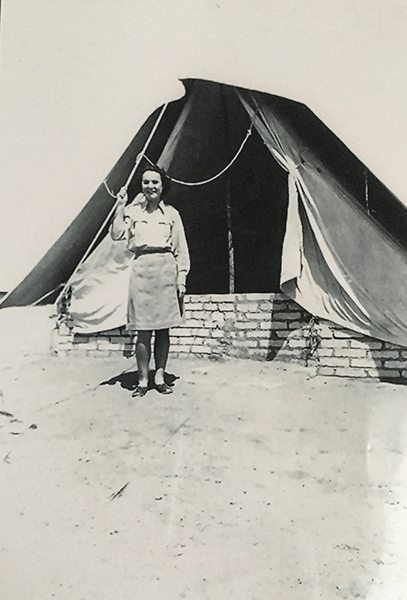

For the next two years, Iris slept in a tent village pitched on the sand.

For the next two years, Iris slept in a tent village pitched on the sand.

The lead image above: Each tent had a stone foundation and a concrete floor.

Just two months after their arrival, D-Day took place on June 6, 1944, the successful invasion of the continent by Allied forces. However, Iris doesn’t remember that this was a cause for celebration. “All we could think about was how many men had been killed or drowned. Today we treat it as a great victory, but it was actually quite a massacre. That’s war, of course.”

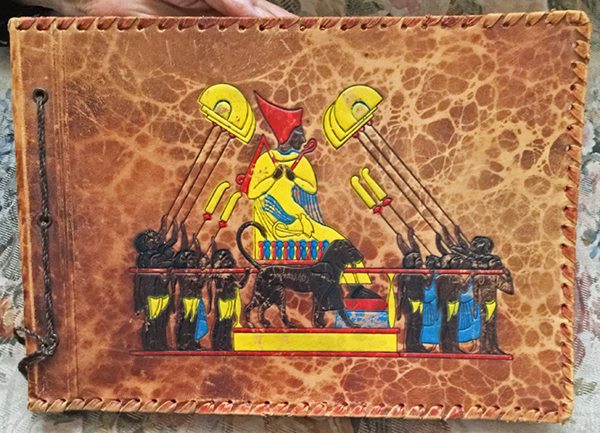

Iris was fortunate to have a friendly commanding officer named Jimmy Schofield. One of the kindest things he did was to purchase a beautiful leather-bound photo album for Iris, which she still cherishes, and fill it with photographs.

Here’s a photo of Iris holding the prized album.

While on their regular leaves, the girls wasted no time in seeing all the sights had to offer. “Kathleen and I took the night train to Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Luxor, Thebes, all over the place.”

While on their regular leaves, the girls wasted no time in seeing all the sights had to offer. “Kathleen and I took the night train to Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Luxor, Thebes, all over the place.”

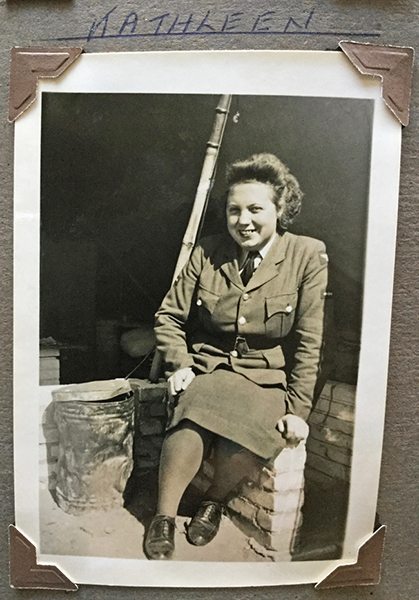

This is a photograph of Kathleen Britain.

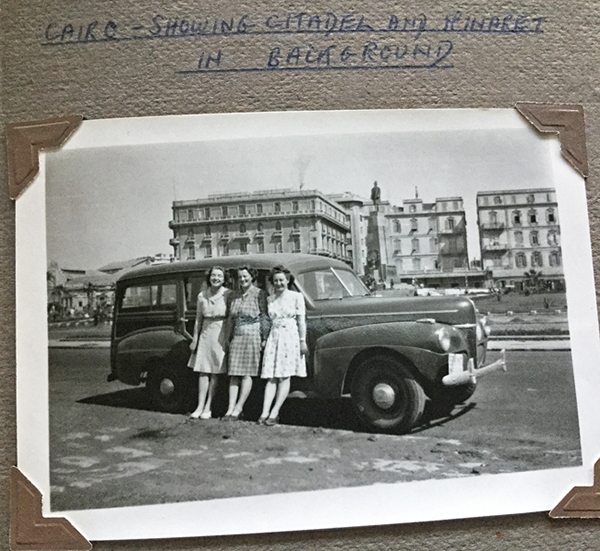

Here are three WAAFs in Cairo, with the citadel and minaret in the background. The girls were allowed to wear “civvies” (civilian clothes), while off duty.

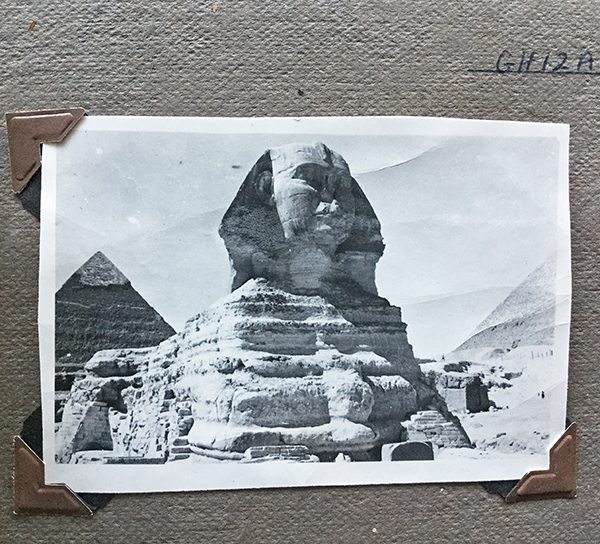

Iris saw Egypt’s most famous monument, the Sphinx at Giza, with the pyramids in the background.

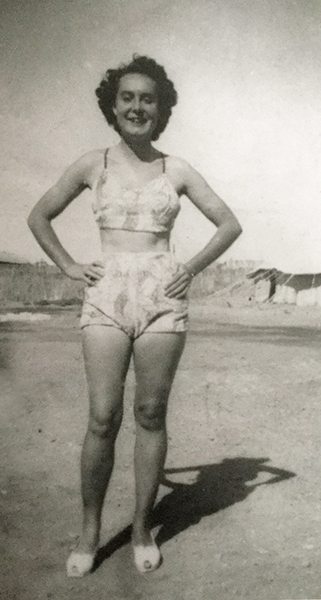

Iris even had a chance to enjoy swimming at several Mediterranean beaches, and here she is looking very trim in a two-piece bathing suit.

Iris particularly enjoyed getting to know the Muslims with whom she worked side by side. “They were absolutely charming,” she said. “They were doing the same work as us. The girls were shorthand typists and they were really good. The men always treated us with great respect.”

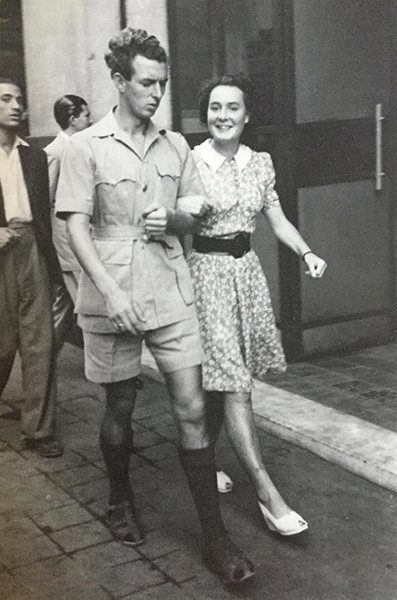

Of course, there was no shortage of men to go out with. “I had many, many dates,” Iris said, “but nothing serious until I met my husband.” Here she is out walking with one of her escorts.

On May 8, 1945, Victory in Europe was declared at last. “All the WAAFs were called into the auditorium, and the Air Vice-Marshall thanked us for our service, since all of us who went overseas were volunteers. One of our girls sang ‘Ave Maria.’ It was very touching. The next day there was a big celebration and victory march through Cairo, early in the morning before it got too hot.”

Two months later, the war came to its final conclusion when the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan. “There was far less celebrating then,” Iris said. “That was a dreadful thing. It seemed such a terrible way to do things.”

War’s end did not mean that Iris could go home, since she had volunteered for two years of service beginning in April 1944. That meant she remained in Egypt until April 1946.

In spite of all the leisure activities, the women worked hard and performed their duties well. Here Iris, standing at the rear, and four of her friends look so happy because they have all just been promoted from the lowest rank of Leading Aircraftwoman to Corporal, allowing them to add two stripes to the sleeves of their uniforms.

Iris Works with Former POWs

The surrender of Japan meant, of course, the liberation of thousands of Allied prisoners who had spent four long years in camps throughout the Far East – not only 140,000 military prisoners, but also another 130,000 civilians, primarily women and children. Altogether the Japanese had established hundreds of prison camps in the Far East, where both servicemen and civilians were treated very badly.

The call went out at Iris’s camp for five WAAFs to volunteer for a new program named RAPWI, (pronounced Rap-wee), the Recovery of Allied Prisoners of War and Internees. Iris volunteered to be one of them.

A temporary camp was set up along the coast at Port Tufik where former troop ships landed every week, filled with thousands of repatriated prisoners of war including men, women, and children, to be outfitted with clothing before continuing their journey to England. Most of them had nothing to wear but rags.

Iris explained: “We used a large wooden hangar, and the Muslim workers built partitions so there was a section for men, women, and children. We had already received shiploads of brand new clothing donated from New Zealand, Australia, Canada and the U.S. The Muslim workers unpacked the bales of clothing and hung it on racks.

After they disembarked, the prisoners came into the hangar and were given enough clothing to see them through the first few months, including new underwear and pyjamas, plus warm outdoor clothing for the winter back in England.

“There was beautiful clothing, most of it new. I remember the first time I ever saw a parka, with a fur-trimmed hood and embroidery around the hem. I thought it was gorgeous.”

After the children received their clothing, they came into the fourth section. Iris was in charge of the toy shop, and each child was given one toy to keep.

“That was the most touching experience. Some of the children had never even seen a toy. A few of them had wooden whistles made of twigs. A man in one of the camps had started a little musical group in an effort to keep them entertained.

“The children would come into my section, emaciated, with swollen bellies due to malnutrition, and I would tell them to choose a toy. I remember one little girl staring at a doll in a push-chair. I said: ‘Sweetheart, you can have that if you want it!’ And she said: ‘For my very own? To take with me on the ship?’ And I said: ‘Yes, darling, you can have it to keep.’

“I felt dreadful when one little boy came in with his father and chose the ceiling fan! I said unfortunately that he couldn’t have the fan, and he started to cry. His father took him outside, and then they came back in, he chose a toy truck instead, with doors that opened at the back. I found a ball to put inside so he would have something in his little truck.”

The WAAFs were also expected to socialize with the prisoners and eat their meals with them. “I remember one man, he was just skin and bone. The table was set for lunch, and there was a big piece of meat on a platter. The man looked at it and his eyes got big, and he grabbed the whole thing and shoved it into his mouth. I guess it was just too much for him. Then he realized what he had done, and he put it back and started to cry.”

The prisoners did not talk about their experience in the camps, Iris said. “They wanted to talk about their future. They talked about seeing their families, going to university. I’ll never forget how grateful they were, especially the women. It was amazing, what they had gone through.”

Iris Meets the Love of her Life

Iris remained at the RAPWI camp from September to December 1945. Near the end of her time there, she attended a YMCA dance and met a handsome young man named Donald Porter from London, a Warrant Officer in the Royal Engineers. He had served for the past four years in Suez, and was just about to leave for home.

“It was love at first sight, really. The next day I went into town with him to buy a leather handbag to take home to his mother. We had a couple of weeks together before he sailed, and then we wrote to each other for the next four months.”

In April 1946 Iris sailed for home at last. Like so many others, she and Donald wasted no further time in getting on with their lives. They were married on July 20, 1946. She was 25 years old; he was 29.

After the War

“While I was away my sister Margaret, who had married a Canadian soldier, had already arrived in Calgary as a war bride. She sent me a Sears catalogue, and I wore it out looking at it! Beautiful frilly curtains, colourful sets of dishes, just the way it used to be in England before the war.

“It was Donald who suggested we immigrate, and at first I didn’t want to. I loved England and I had been away from home for so long. We had our first baby Anne in 1947, and a year later we came to Calgary and we never lived anywhere else again.”

Don found work immediately as a sheet metal worker, and the couple had three more children: Roy and Kerry, both retired teachers; and Diana, who works at the Law Foundation in Calgary. Anne is a nurse in High River, Alberta.

After the children got older, Iris worked part-time in the shoe department at Sears Department Store in downtown Calgary for 29 years, from 1967 to 1996. It comes as no surprise to find that Iris was a loyal member of the Sears staff, appreciated by both her customers and her fellow workers.

Both she and her husband became Canadian citizens. “My husband loved Canada so much that he became a citizen in 1950. I took a little longer and applied for citizenship in 1975.”

Donald Porter died in 2006. Today Iris still lives in the house near Heritage Park in Calgary where she has lived for the past 38 years.

Iris, thank you so much for your courage and dedication to the land of your birth, and to the Allied victory that our countries shared.

– Career journalist and bestselling author Elinor Florence of Invermere has written two wartime books. Her novel Bird’s Eye View tells the story of an idealistic Saskatchewan farm girl who joins the Royal Canadian Air Force and becomes an interpreter of aerial photographs. My Favourite Veterans is a non-fiction collection of interviews whose stories appeared previously on e-KNOW, including Cranbrook’s own Bud Abbott.

Elinor’s new novel Wildwood, about pioneer life in the Peace River, Alberta region, will appear in February 2018. It is available for pre-order now at a reduced price on Amazon. For more information about all three books, visit Elinor’s website at www.elinorflorence.com or call her at 250-342-1621.