Home »

Study says gravel-bed rivers an ‘ecological nexus’

Gravel-bed river floodplains are some of the most ecologically important habitats in North America, according to a new study by scientists from the U.S. and Canada.

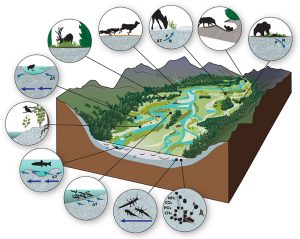

Their research shows how broad valleys coming out of glaciated mountains provide highly productive and important habitat for a large diversity of aquatic, avian and terrestrial species.

The paper ‘Gravel-Bed River Floodplains are the Ecological Nexus of Glaciated Mountain Landscapes’ published today in Science Advances is the first interdisciplinary research at the regional scale to demonstrate the importance of gravel-bed rivers to the entire ecosystem.

Dr. Ric Hauer, professor and director of the Center for Integrated Research on the Environment at the University of Montana, leads a group of authors who looked at the full continuum of species and processes supported by gravel-bed rivers, from microbes to bull trout and from elk to grizzly bears.

Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative (Y2Y) co-founder and strategic advisor Harvey Locke and Y2Y board member and University of Montana professor Mark Hebblewhite are co-authors. The team of scientists on the study also includes UM professors Vicky Dreitz, Winsor Lowe, and Cara Nelson; Clint Muhlfeld, research aquatic ecologist from the U.S. Geological Survey; Professor Stewart Rood from University of Lethbridge; and biologist Michael Proctor of Birchdale Ecological.

Gravel-bed rivers are found throughout the world in mountainous regions, but the complexity of how they benefit a wide range of species that use the whole landscape has not been extensively studied before now.

The research underlying the study was done through many years of field work in the Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y) region, which stretches from Yellowstone National Park north into Canada’s northern Yukon Territory.

In the Yellowstone to Yukon region gravel-bed river plains support more than half the region’s plant life; more than 70% of the region’s bird species use the river floodplains while deer, elk, caribou, wolves and grizzly bears use the floodplains for food, habitat and important migration corridors.

“Gravel-bed rivers are found at the headwaters of all the major rivers of the west,” Locke said, “including the Colorado, Missouri, Bow, North Saskatchewan, Columbia, Fraser, Peace, Yukon, and Mackenzie rivers.”

“If we think about the Flathead River for example, flowing from British Columbia into the U.S. and along the western edge of Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park,” Hauer said, “we might wrongly imagine that the river is only water flowing in the channel. But, these gravel-bed systems are so much more than that. The river flows over and through the entire floodplain system, from valley wall to valley wall, and supports an extraordinary diversity of life. The river is so much bigger than it appears to be at first glance.”

Gravel-bed river systems provide complex habitats for species because of the system’s ever-changing features: gravel and cobbles that move with flooding, scoured and changing river channels, and a constant flow of water into and out from the gravels of the river. This water extends across the U-shaped valley bottom often hundreds of meters or more from the river channel, and supports a complex food web that includes aquatic species as well as a vast diversity of avian and terrestrial species. These processes are driven by the river’s changes in volume throughout the year.

The gravel-bed rivers also provide essential connectivity across the landscape for both terrestrial and aquatic organisms, which is critical in a time of climate change.

These floodplains also are some of the most endangered landforms worldwide. Human settlement, agriculture, industry and transportation often occur in flat, productive river valleys. While there are many protected areas in the Y2Y region such as Yellowstone and Banff national parks, humans have altered the structure and function of the gravel-bed river floodplains outside, as well as inside these protected areas.

“The single best thing we can do for nature across the entire Y2Y region is to keep gravel-bed rivers in a natural condition, including allowing the essential natural process of flooding,” Locke said.

“The increasing pressures of climate change mean that species need continued access to intact gravel-bed river ecosystems in order to survive,” Hauer said. “These systems must be protected and those that are already degraded must be restored.”

The paper, “Gravel-Bed River Floodplains are the Ecological Nexus of Glaciated Mountain Landscapes,” is published online in Science Advances.

Abstract and article: Gravel-bed River Floodplains are the Ecological Nexus of Glaciated Mountain Landscapes available on Science Advances.

Lead image: Flathead River at the U.S./Canada border. Photo by Harvey Locke

e-KNOW