Home »

Out of chaos, comes the gift of sight

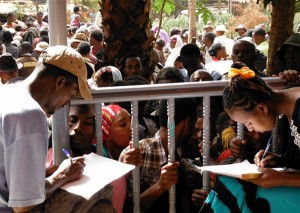

And suddenly there we were, facing a milling crowd of at least 250 blind people and their helpers at a Rotary eye camp in Dembi Dolo, a small town on the far west side of Ethiopia where eye care hardly exists and the anxious people we met regarded us as their only hope to regain their vision.

You could cut the anticipation in the air with a knife.

But, truth to say, some of us were pretty anxious ourselves. At least I was. The scene was chaotic. Just squeezing up the stairs past the patients to get inside the concrete clinic took some delicate maneuvering. Once inside, I found myself in a small bunker of a room that turned out to be the sterilization unit next door to the small operating theatre. Meanwhile, the other volunteers fanned out to do a variety of duties including crowd control, sight assessments, putting drops in eyes and separating surgery patients from optometrist patients as well as testing visual acuity with an eye chart on the side of a building outside and somehow keeping everything orderly and the patients happy as they waited hours in the muggy, Ethiopian heat.

No small matter.

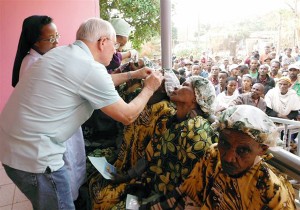

On that busy opening day, we didn’t get a surgery done until close to noon and only 26 for the day (later close to 50-a-day). But slowly the chaos began to subside as ophthalmologist surgeons Dr. James Guzek from Tri-Cities, Washington and Dr. Samuel Bora from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia began to hit their stride. The crowd outside remained unruly most of the first day, which was to be expected, because not everyone could be seen right away and there were some whose problems were inoperable. But even in situations like this they still wanted “to see the doctor,” and if nothing else, “just be touched,” says Guzek. And “touched” they were every day no matter how long it took.

On the second day, an armed guard was called in and his uniform, more than his automatic weapon, did more to calm the crowd than anything else. Just the same until nearly the end of the clinic a week later, there were always lots of people milling about, clutching the banister of the stairway, inching their way closer to the front of the line until they paid around 15 birr (about a dollar American) for a procedure that would cost thousands on this side of the globe. However, even by Ethiopian standards, where the Gross National Income is $859 annually, the 10th poorest in the world according to the International Monetary Fund, this is still a considerable amount of money and helps people to appreciate what’s being done for them

Ethiopians tend to be very stoic people and they had to be for a Third World clinic like this to succeed. Even when the bandages were removed from their eyes the next day, the reaction was more subdued than expected. Often it was no more than a shaking of the head, a suppressed gasp and then their faces would light up when they recognized a loved one they hadn’t seen in years. I tried to interview one, which was difficult considering the language barrier and the trauma of surgery. All the 50-year-old lady would say was she felt “o.k.” and she said it over and over again finally adding what was translated as “God bless the doctor.” Ethiopia is a religiously diverse country and spiritualism runs deep.

I’ll never forget an experience I had about the fourth day when I decided to walk the dusty road back to the convent instead of taking the Land Cruiser. I passed the tin-roofed shacks that most of the people live in as well as many small shops with electrical wires dangling from them connected by Christmas style lights that would light up intermittently when the power came on and reflect off the ubiquitous, corrugated, tin roofs.

Suddenly, I felt I was being followed and I turned around to see a girl in a bright orange T-shirt following me. She was 10-years-old at most and smiled shyly and kept following until the next thing I knew she had slipped her hand in mine. A little flustered I kept walking and we met several other children and before I knew it we were all holding hands, almost a dozen of us, and walking down that dusty, red road like the Pied Piper leading his merry troupe. It was near dusk and I didn’t even have my camera with me, but when I finally pulled away from the children there was a lump in my throat that would have choked a horse.

We have so much; they, so little.

That experience will remain with me forever and so will many other memories and feelings that we all experienced. I couldn’t help but feel proud that I played a very small role in an endeavor that’s literally helping the blind to see thanks to some dedicated professionals as well as volunteers who traveled half-way around the world to help them and the Rotary movement with its credo of “service above self” and all those who donated to the cause.

And the cause is going to continue as Dr. Guzek and others explain in the final part of this series.

– Gerry Warner is a retired journalist and a Cranbrook City Councillor who recently participated in a Rotary eye camp in Dembi Dolo, Ethiopia.